One of the most interesting and probably most consequential books on China to come out in recent years is Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China by Michael Beckley and Hal Brands. If you’ve missed it, the authors basically argue the following:

Based on historical record, the most dangerous great powers are not the ones that are rising, but the ones that are declining - powers that know they’ve already peaked, and they think their best shot at gaining more power is right now.

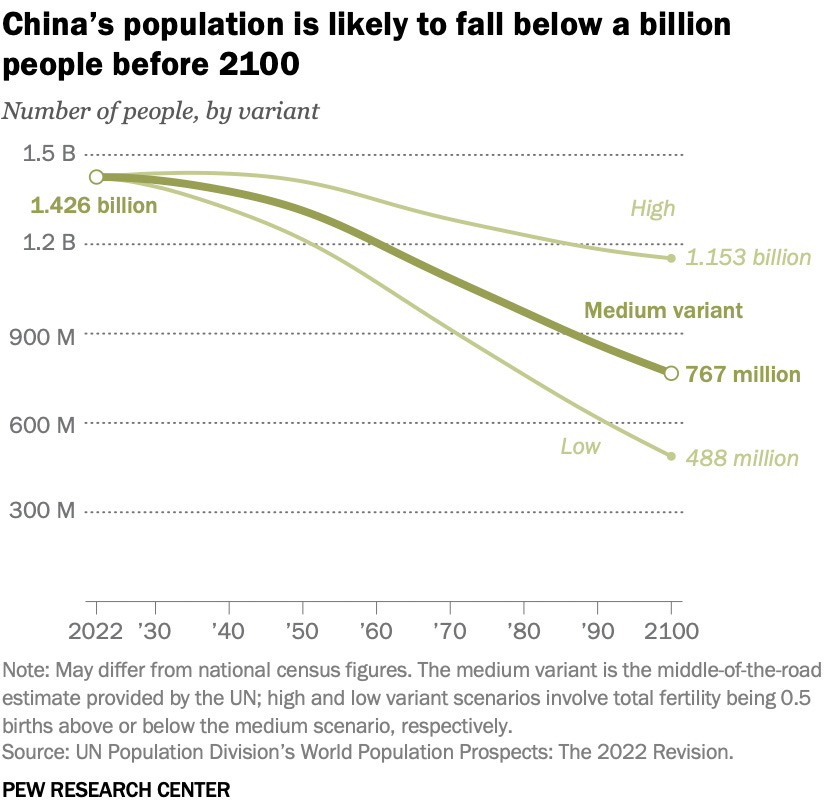

China, they argue, is in exactly that position. With a slowing economy and a shrinking population, it’s no longer a rising power, but a declining one.

And because of that, if China ever wants to take Taiwan by force, the window is closing fast. It has to act while it still can - which makes the late 2020s the most dangerous period for U.S.-China relations in decades.

It’s a really compelling theory, and Beckley and Brands make a strong case, plus they are both excellent thinkers on geopolitics and Michael Beckley is a fantastic China expert (I interviewed Michael about his thesis on my podcast - it’s one of the best conversations I’ve ever had with anyone) . But the argument still hinges on one major assumption: that China is declining. That the future is going to be harder than the present, and that its relative position to the U.S. will only get weaker. But whether that’s true - and more importantly, whether Chinese leadership thinks it’s true - is now becoming a lot less clear than how it seemed just a few years ago.

In 2022 when the book came out, the idea of a “peak China” looked very, very accurate and the years that followed basically turned it into the mainstream view of China’s trajectory. The property sector, long a pillar of the economy, was collapsing, as China’s biggest developers (remember Evergrande?) were defaulting on debt and leaving behind unfinished “ghost cities”. Youth unemployment hit 20% before the government stopped publishing the data. Entire cities were locked down under zero-COVID. Factory output dropped, consumer confidence collapsed, foreign investors were pulling out and headlines were full of talk about China’s “Lehman moment,” a looming demographic crisis, and comparisons to Japan in the 1990s but on a much larger scale. Overall, China’s situation looked pretty apocalyptic.

Meanwhile, the U.S. looked relatively strong. The post-COVID recovery was very strong and its economic growth outpaced most of the West. The U.S. seemed to be absolutely dominant in the emerging and hugely important AI sector, the hype was fueling a tech rally, and the Biden administration was still projecting some sense of global leadership. Taiwan was receiving more attention and support than ever before, and being tough on China and preparing for a confrontation became basically almost the only policy with broad bipartisan support in U.S. politics.

So at the time, the “closing window” argument made a lot of sense. China looked like a country whose power had already peaked and if you were sitting in Beijing, convinced that unification with Taiwan was your absolute priority, there was a real logic in moving sooner rather than later, while the gap was still manageable.

But by mid-2025, the picture has shifted again.

The U.S. under Trump’s second term looks a lot more politically and economically unstable than it did two years ago - and more unstable than in my entire lifetime. The U.S. have unsuccessfully declared and called off a trade war with the rest of the world, started a trade war with China where it found itself with a much weaker hand than anyone expected, it’s playing with the idea of destroying the global reserve currency status of the dollar, it’s doing everything it can to convince allies everywhere that they can no longer rely on the United States for help and overall, hugely damaging its global image.

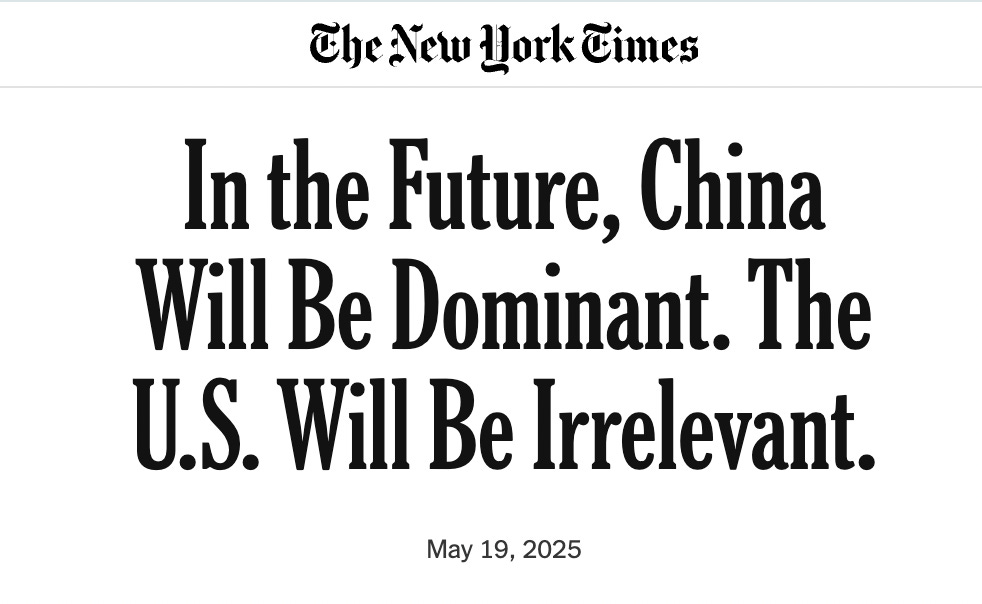

And meanwhile, the mainstream media narrative on China has shifted as well. The headlines moved from China’s collapse to China’s dominance in manufacturing, EVs, and industrial capacity. And thanks to Trump’s unpredictability, Beijing now (at least on the surface) almost seems like the more stable superpower out of the two - something that would seem unthinkable not that long ago.

Op-Ed on China’s Economy in New York Times in mid-2024

Op-Ed on China’s Economy in New York Times in mid-2025

The bizarre thing about all of this is that the fundamentals haven’t actually changed all that much and Michael Beckley’s and Hal Brands’ arguments would make just as much sense today. China still has major, structural economic issues: serious demographic problems, a fragile property sector, and persistent youth unemployment. The U.S. still has major structural advantages: innovation, technology, alliances. But the vibe, the perception, about who is going up and who’s going down has still shifted quite radically. And the vibe can matter more than people like to admit - because when it comes to big-picture assessments like the rise and fall of major powers, it’s often just as much about hard facts as it is about the stories and the perceptions that we tell ourselves about them.

And the issue with the “closing window” argument is that it does rest on an assumption about trajectories: that China is going down, and the U.S. isn’t. But even though the facts haven't changed all that much, that assumption is still a lot harder to hold onto now than it was just a couple of years ago. Not because either side has solved their structural problems, but because it’s harder to make a confident call about which of the two is actually in decline or whether that’s even the right framework anymore.

We’ve gone from years of obsessing over China’s rise to suddenly talking about its collapse, and now we seem to be circling something in the middle, a version of the world where neither power is on a clear trajectory, and both are dealing with problems they can’t really fix. China’s growth model doesn’t work anymore and its economy is dealing with a bunch of wrong decisions from the past - but it is the new manufacturing superpower. The U.S. is electing leaders who want to destroy the global system that worked in its favor for so long - but it still has the most innovative entrepreneurial ecosystem in the world. Instead of one clearly rising and one clearly declining power, locked in a confrontation, we might be watching two semi-dysfunctional giants trying to figure out if they still have time left on the clock.

Which makes the real question less about military readiness or economic fundamentals, and more about interpretation. The entire debate around whether China will invade Taiwan and when depends on how Xi Jinping and his inner circle read the direction of travel. Do they believe they’re running out of time? Or do they think the United States is?

So is China running out of time to invade Taiwan and does it mean that a great power war is becoming an imminent threat?

Well, if Beijing sees itself as weakening, then launching a high-risk war to secure a long-term strategic goal might make sense to them. Not because it’s likely to succeed (if the United States joins the fight, it’s almost guaranteed not to), but because the alternative - doing nothing and watching your position erode - is even worse if you are someone like Xi Jinping who sees his legacy as restoring China back to its former greatness.

But if Xi thinks the U.S. is in structural decline - militarily overstretched, politically divided, increasingly isolationist - then the best move is to wait. Let Taiwan drift further from the American orbit. Let the U.S. exhaust itself elsewhere. And wait as long as it takes for when a better opportunity will emerge.

And that’s the problem. We have no real idea which version of the story Xi believes and we don’t know if he sees China as rising, peaking, or holding on by its fingernails. And neither, it seems, does anyone else right now.

You don’t have to wait till 2100. China’s real population is inflated. If you take India’s growth model as a benchmark for a developing nation, the Chinese population is likely to be around 800-900 million at most. Current Chinese population figures like its annual GDP cannot be trusted. So China’s demographic decline is even faster. The Chinese earlier growth is predicated on the continued availability of a large youthful labor and domestic consumer market. As we already know, China’s consumer market is woefully weak, and much of the consumer spending is already tied up in the debt-ridden property market. The cost of raising kids in China is very, very, very expensive. This has a huge impact on China’s population growth.

The report by YuWa Population Research Institute stated that the national average to raise a child in China till the age of 18 is about 538,000 yuan (US$74,600). This includes nanny and childcare fees, money spent on school and educational materials as well as extracurricular activity fees.

That’s around 6.3 times the country’s per capita GDP and “almost the highest in the world”, the report said.

Also highlighted - how China’s rate exceeds other countries such as neighboring Japan (4.26 times), the United States (4.11 times), France (2.24 times) and Australia (2.08 times). South Korea claimed the top spot, with the cost coming in at 7.79 times the country’s GDP per capita.

At the moment, the Chinese EV market is heading towards an Evergrande-esque meltdown. The Chinese production model is not market-driven which typically provides throttling forces to adjust industrial input and output. China’s economic model is both ideologically and party-state-driven.

Currently, China is propping up zombies unprofitable state enterprises, and companies to avoid mass layoffs, unemployment, and unrest. Lots of shadow banking debts and lots of money printings.

I’m not sure the U.S. is necessarily in decline, at least not in the short term. Based on how Americans have voted in recent elections, it’s likely that they’ll choose a competent leader in the next one.

That said, the country has been swinging between completely different types of administrations. What worries me in the long run is that Americans have twice elected someone who was pretty clearly bad for the country.

As for Taiwan, everything depends on the U.S. If the U.S., together with Japan, can maintain strong military deterrence, then I don’t think a war is likely anytime soon.